更多語言

更多操作

AliceMargatroid(留言 | 貢獻) (重定向页面至马克思) |

AliceMargatroid(留言 | 貢獻) (已移除至马克思的重定向) |

||

| 第1行: | 第1行: | ||

{{Infobox person | |||

| honorific_prefix = | | honorific_prefix = | ||

| name = 卡尔·马克思 | | name = 卡尔·马克思 | ||

於 2022年8月16日 (二) 07:09 的最新修訂

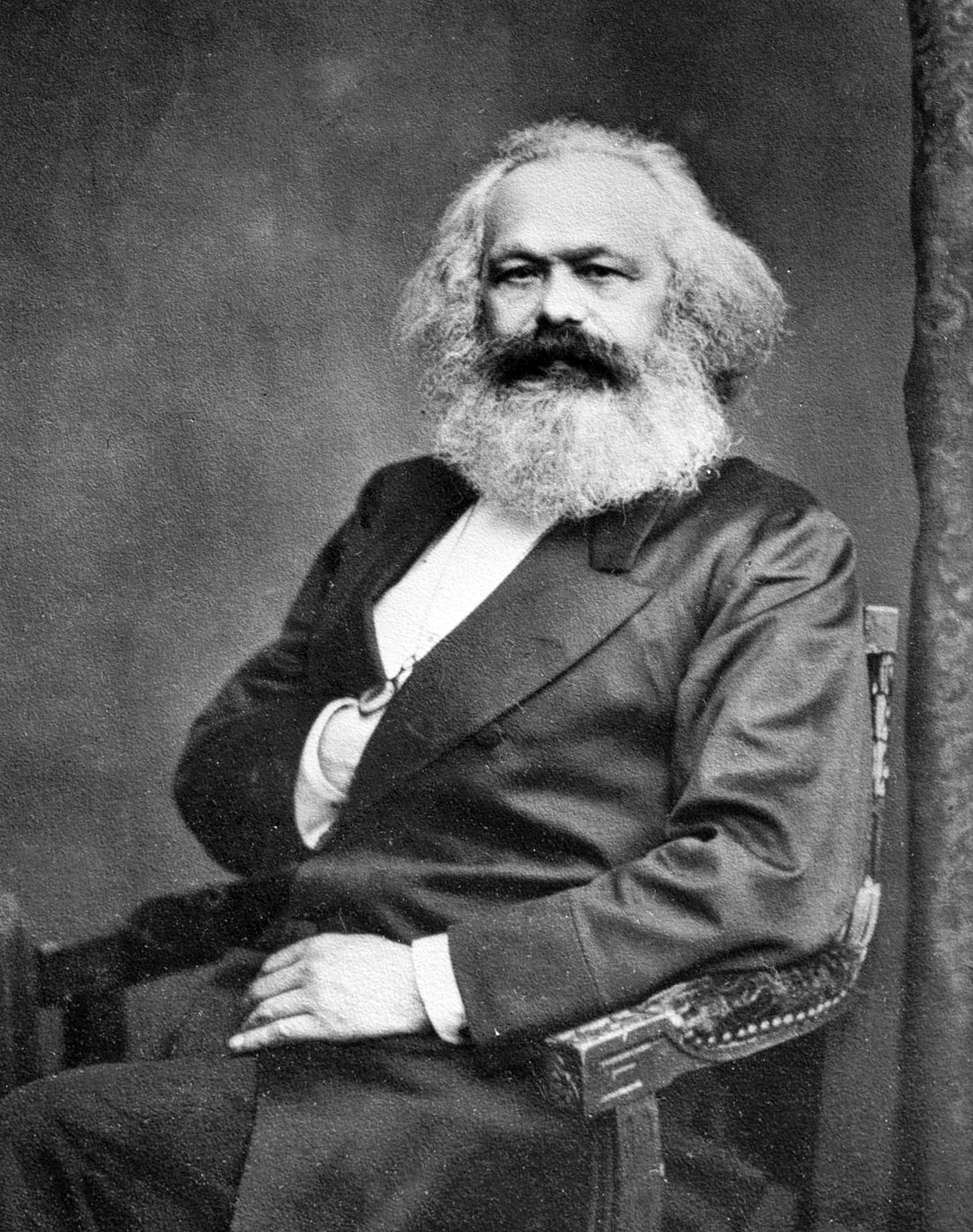

卡爾·馬克思 Karl Marx | |

|---|---|

馬克思同志畫像。 | |

| 出生日期 | 卡爾·海因里希·馬克思 1818年5月5日 德意志聯邦, 普魯士王國, 特里爾 |

| 去世日期 | 1883年3月14日 英國倫敦 |

| 國籍 | 普魯士 (1818年–1845年) 無國籍 (1845年後) |

| 作為 | 創立馬克思主義 |

| 研究領域 | 哲學, 科學, 政治經濟學, 歷史 |

卡爾·馬克思 ,(1818年5月5日-1883年3月14日), 德國哲學家、經濟學家、歷史學家、社會學家、政治理論家和社會革命家。他和他的親密戰友恩格斯一起,基於辯證唯物主義發現了人類社會發展規律,創立了馬克思主義。

馬克思是共產主義運動最重要的思想家。他強調了資本主義中的矛盾和內在剝削,提出了社會主義經濟模式。他最著名的作品是1848年與恩格斯合著的《共產黨宣言》和1867年完成的《資本論》,這兩部作品都具有巨大的國際影響力。

生平[編輯 | 編輯原始碼]

早年生活[編輯 | 編輯原始碼]

馬克思於 1818 年 5 月 5 日出生在普魯士南部有約一萬一千人口的小鎮特里爾,靠進法國。[1] 1794年到1815年,這座小鎮曾屬於法國, 拿破崙戰敗後被普魯士吞併。[2]馬克思是海因里希和亨麗埃特·馬克思的第三個孩子,有七個兄弟姐妹。到1847年,馬克思29歲時,除了他的三個姐妹蘇菲(1816 - 1886),艾米莉(1822 - 1888)和路易絲(1821 - 1893)之外,其餘都已經死於肺結核。[3]

卡爾·馬克思(Karl Marx)的家庭是特里爾一個富裕的小資產階級家庭,他的父母都有猶太血統,但他的家人在1824年皈依了新教。其父親海因里希是一位富裕的律師,在特里爾有一定名氣,也積累了一定財富。[4][5]

卡爾·馬克思和他的妹妹蘇菲結識了埃德加和燕妮·馬克思,後者後來成為馬克思的妻子。這段感情要麼始於在和馬克思在同一學校學習的埃德加,要麼始於他們父親之間。.[6]馮威斯伐倫家族也是一個小資產階級家庭,[7] 年輕的卡爾與燕妮的父親約翰·路德維希·馮·威斯伐倫男爵是朋友,他的思想對馬克思產生了影響。[8]

從 1830 年到 1835 年,馬克思就讀於弗里德里希·威廉中學,這是一所為學生上大學做準備的公立中學。 在那裡他跟隨幾位老師學習,其中一些老師對政治現狀持批評態度,其中包括學校主任約翰·雨果·維滕巴赫。[9][10] 當時,自由主義被革命理想和對法國大革命的浪漫情懷聯繫在一起,這兩者都為普魯士政府所厭惡。 特里爾學院(Trier Gymnasium)當時只招收男學生[11] 而馬克思在那兒學習了希臘文、拉丁文和法文[10]

大學階段[編輯 | 編輯原始碼]

在特里爾學院以優異的成績畢業後,馬克思進入了大學,從 1835 年到 1836 年在波恩大學學習了兩個學期。馬克思的父親厭惡兒子酗酒和放蕩不羈的生活方式,並說服他轉學到當時著名的柏林大學 。 在那裡,他學習了法律,主修歷史和哲學,並於 1841 年完成了大學課程,發表了一篇關於伊壁鳩魯哲學的博士論文。 當時的馬克思看來是一個黑格爾唯心主義者,與布魯諾鮑威爾等人一樣,屬於「左派黑格爾主義者」的圈子。[12]

晚年經歷[編輯 | 編輯原始碼]

意識形態來源[編輯 | 編輯原始碼]

馬克思最根本的思想來源是德國古典哲學、英國政治經濟學和法國空想社會主義。[15]

主要德國古典哲學來源:

主要英國政治經濟學來源:

主要法國空想社會主義來源:

參考[編輯 | 編輯原始碼]

- ↑ 「In 1819, Trier had hardly more than 11,000 inhabitants; furthermore, about 3,500 soldiers were stationed in Trier (Monz 1973: 57). This was not an especially large population, even if one takes into consideration that back then most people lived in the countryside and cities had far fewer inhabitants than today. [...] The Trier in which Marx grew up was characteristically rural; it had only two main streets, the rest of the town consisting of side alleys and little streets.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (pp. 39-40). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「In 1794, Trier was occupied by French troops. Revolutionary France had not only beaten back the monarchist powers but had made considerable territorial conquests. [...] After Napoleon’s failed Russian campaign, French rule ended. In 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, Catholic Trier, along with the Rhineland, was awarded to Protestant Prussia.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (pp. 39-40). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「Karl was not his parents』 first child; in 1815, their son Mauritz David and in 1816 daughter Sophie had been born. However, Mauritz David died in 1819. In the years following, further siblings were born: Hermann (1819), Henriette (1820), Louise (1821), Emilie (1822), Caroline (1824), and Eduard (1826), so that Karl grew up with seven siblings total. However, not all of them would go on to live long lives: Eduard, the youngest brother, was eleven when he died in 1837. Three other siblings were hardly older than 20 at the time of their death: Hermann died in the year 1842, Henriette in 1845, and Caroline in 1847. In all cases, the cause of death was given as 「consumption」 (tuberculosis), a widespread illness in the nineteenth century. The three remaining sisters lived considerably longer; they also survived their brother Karl. Sophie died in 1886, Emilie in 1888, and Louise in 1893.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (p. 35). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「Marx’s father was a well-regarded lawyer in Trier, and his income allowed his family a certain affluence. Both the house on Brückengasse (today Brückenstraße), which the family rented and in which Karl was born,16 as well as the somewhat smaller, but centrally located house on Simeonstraße that the family purchased in the autumn of 1819 and in which young Karl grew up, were among the better bourgeois homes of the city. (p.35)

[...]

The center of social life in Trier was the Literary Casino Society (Literarische Casinogesellschaft) founded in 1818. Its statutes determined its purpose to be 「maintaining a reading society connected to an association location for the convivial enjoyment of educated people」 (quoted in Kentenich 1915: 731). In the Casino building, completed in 1825, there was a reading room that also contained several foreign newspapers. Balls and concerts, and on special occasions banquets, were regularly held (see Schmidt 1955: 11ff.). The sophisticated bourgeois stratum and the officers of the garrison belonged to the Casino. Karl’s father, Heinrich Marx, was one of the founding members. Similar societies, often with the same name, also arose at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century in other German cities; they were important focal points for the emerging bourgeois culture. Critique of existing political conditions was also articulated here. (pp. 41-42)」

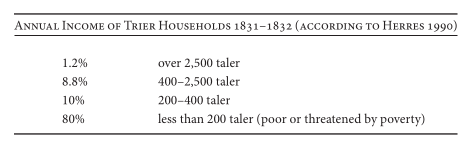

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (pp. 35-42). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「Professional success was also reflected in a certain level of affluence. In 1819, Heinrich Marx was able to buy a house on Simeonstraße. According to the tax information evaluated by Herres, Heinrich Marx was assessed in 1832 as having an income of 1,500 talers annually, thus belonging to the upper 30 percent of the Trier middle and upper class that had a yearly income of more than 200 talers. Since this middle and upper class only comprised around 20 percent of the population, the Marx family, in terms of income, belonged to the upper 6 percent of the total population. With this income, the family was also able to accumulate a certain level of wealth, owning multiple plots of land used for agriculture, among which were vineyards. For wealthy citizens of Trier, ownership of vineyards was a popular retirement provision. The Marx family also employed servants. In the year 1818, there was at least one maid; for the years 1830 and 1833, 「two maids」 are documented.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (pp. 67-68). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「Eleanor reports that among Marx『s earliest playmates was his future wife, Jenny von Westphalen, and her younger brother Edgar. The latter attended the same school as Marx and also received confirmation along with him on March 23, 1834. How the children『s friendship came about and when it began, however, remains unknown. We know that Marx『s older sister Sophie was friends with Jenny, but whether it was the two girls or the two boys Karl and Edgar who first made friends, or whether the children『s friendship was first initiated through the friendly relationship between their fathers, is not known.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (p. 36). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑

「Ludwig von Westphalen and Heinrich Marx had annual incomes of 1,800 and 1,500 taler, respectively.」

「Ludwig von Westphalen and Heinrich Marx had annual incomes of 1,800 and 1,500 taler, respectively.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (p. 45). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「Eleanor also discloses that the young Karl was intellectually stimulated primarily by his father and his future father-in-law, Ludwig von Westphalen. It was from the latter that he 「imbibed his first love for the 「Romantic」 School, and while his father read him Voltaire and Racine, Westphalen read him Homer and Shakespeare.」 The fact that Marx dedicated his doctoral dissertation rather emotionally to Ludwig von Westphalen in 1841 demonstrates how important the latter was to him.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (p. 36). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「The towering presence of the Trier gymnasium was its director of many years, Johann Hugo Wyttenbach (1767–1848). He was also an archaeologist and founder of the Trier city library. In 1804, Wyttenbach was already director of the French secondary school; he remained director of the gymnasium until 1846. His thinking was strongly influenced by the Enlightenment; in his earlier years, he was an adherent of the French Jacobins. He maintained his liberal and humanistic ethos even under Prussian rule.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (p. 97). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 10.0 10.1 「When the young Karl started gymnasium in 1830, Wyttenbach was sixty-three years old. Most teachers were considerably younger, and as can be gleaned from the fragmentary information of the surviving records, at least a few of them had rather critical attitudes toward the reigning social and political conditions and were observed with distrust by the Prussian authorities.

First and foremost to be named in this regard is Thomas Simon (1793– 1869), who taught French to Karl at the Tertia level. [...] He had 「turned toward the concerns of the poor, neglected people,」 since as a teacher he had seen daily that 「it was not the possession of cold, filthy, minted money that makes a human being a human being, but rather character, disposition, understanding, and empathy for the weal and woe of one’s fellows」 (quoted in Böse 1951: 11). In 1849, Simon was elected to the Prussian house of representatives, where he joined the left. His son, Ludwig Simon (1819–1872), also attended the gymnasium in Trier and took the Abitur exams a year after Karl. [Ludwig] was elected to the national assembly in 1848. As a result of his activities during the revolutionary years of 1848–49, the Prussian government brought multiple legal proceedings against him and convicted him in absentia to death, so that he had to emigrate to Switzerland.

Heinrich Schwendler (1792–1847), who taught French to Marx at the Obersekunda and Prima levels, was suspected in 1833 by the Prussian government of being the author of an insurgent leaflet; he was accused of 「poor character」 and of 「familiar relationships to all the fraudulent minds of the local city.」 In 1834, a ministerial commission warned of the 「pernicious orientation」 of Simon and Schwendler, and in 1835, the provincial school council regarded his dismissal as desirable, but could not find a sufficient reason (Monz 1973: 171, 178).

Johann Gerhard Schneeman (1796–1864) had studied classical philology, history, philosophy, and mathematics; he published numerous contributions on the archaeology of Trier. At the Tertia and Obersekunda levels, he taught Karl Latin and Greek. In 1834, Schneeman also participated in the singing of revolutionary songs at the Casino and was interrogated by the police as a result.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (pp. 98-99). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ 「Marx was a student for six years. There are serious differences between student life then and as it exists today. Perhaps the most noticeable back then was that there were no female students or professors; universities were purely male institutions and would remain so for quite a while. Whereas in Switzerland women could enroll at the University of Zurich beginning in the 1860s, it wasn’t until the end of the nineteenth century that women were admitted as regular students to German universities.」

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (p. 122). New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ Lenin (1914). Karl Marx: A brief biographical sketch with an exposition of Marxism. marxists.org link

- ↑ "The Last Years of Karl Marx". Midwestern Marx.

- ↑ "Book Review: The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography. By: Marcello Musto. Reviewed By: Carlos L. Garrido". Midwestern Marx.

- ↑ Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1913-03) The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism